Biography | Bound for Europe

It is hard for anyone today to image the excitement and sense of anticipation Nellie Armstrong felt as she boarded the Bengal at Port Melbourne on March 11, 1886.

When waving goodbye to family and friends one wonders what her reaction would have been had she known it would be another 16 years before her return to Australia.

For David Mitchell the trip to the old country was to carry out his official duties as Victorian Commissioner for the Indian and Colonial Exhibition and then for the last time, visit his home in Scotland.

Nellie, Charles and their small son had other ambitions in mind.

Nellie had letters of introduction from influential people in Melbourne tucked away. Charles probably saw the voyage as a chance to spend time with his son before visiting his own family, particularly his mother who was now living in England.

Arriving in Europe

Writing in Melodies and Memories, Nellie recalled her first images of London:

“Tulips in the Park – tulips golden and crimson and yellow – that is my first memory of London as I saw it on the 1st of May, 1886. We had come through Tilbury, and the sight of the grey skins, the dirty wharves, the millions of grimy chimney-pots, had struck a chill to my heart.” (1)

Her gloom was soon lifted as she saw gay handsome cabs, vast shops, crowds of people and the tulips in Hyde Park.

David Mitchell had taken a home at 89 Sloane Street and the family had no sooner moved in than Charles wanted to take his family to meet his mother at Rustington in Sussex.

Lady Armstrong had been ill but warmly welcomed her son and his new family and she soon had a happy relationship with Nellie. (2)

Back in London, Nellie armed with her letters of introduction, tried to arrange appointments with teachers and musicians. The response was depressing as she was just one of many from all over the world wanting auditions and being from the colonies didn’t help her cause.

While depressed about auditions Nellie was able to hear all those stars she had only read about.

On May 4 at the opening of Indian and Colonial Exhibition, she heard Canadian Emma Albani sing ‘Home sweet home’. A few days later she heard Swedish star Christine Nilsson and a recital by Madame Adeline Patti. (3)

Hearing Patti made Nellie realise the work she had to do to be as good as her.

Rejection

Her first audition was with Arthur Sullivan. After singing Ah! Fors’ ‘lui he simply said if she went on studying for another year, ‘there might be some chance that we could give you a small part in the Mikado – this sort of thing.’ (4)

Nellie hid her disappointment as she did not want to do light opera.

The next person she saw was Brinsmead who was one of the leading makers of pianos at the time.

After playing the piano and singing he paid her a compliment:

‘The timbre of your voice is almost as pure as the timber of my pianos,’ (5)

The famous singing teacher Alberto Randegger heard Nellie but said he had no time to teach her, perhaps in a few months he could give her a few hours a week.

The last person Nellie went to see in London was Wilhelm Ganz who was enchanted by her voice and arranged a concert for her.

Her first appearance on the stage in London took place on the afternoon of June 1, 1886 at Princes Hall, Piccadilly in an Emil Bach concert. She sang ‘Ah! Fors’ ‘lui’ with orchestral accompaniment and Ganz conducting. (6)

‘There was a certain amount of genteel applause, congratulations from Ganz, and the concert was over. Nobody of any importance had been there. No step had been taken in my progress to fame. And this was perhaps the most disheartening experience of all. (7)

Ganz organised for Nellie to also sing the following night in the Freemasons’ Hall at a dinner of the Royal General Theatrical Fund. (8)

Mathilde Marchesi

Nellie had already written to Mathilde Marchesi, the leading opera teacher in Europe, as she had a letter of introduction from Madame Wiedermann-Pinschof who had been a pupil of Marchesi in Vienna but the appointment wasn’t until July.

While Nellie was trying to be successful on the stage, Charlie had signed on with the Prince of Wales’ Leinster Regiment (Royal Canadians) on May 29, 1886.

In 1881 this battalion’s home depot became Birr, in County Offaly, Ireland and was regarded as Charles’ ‘home’ battalion. (9)

During July Charles and Nellie was to visit and stay with her brother-in-law at Gallen Priory and didn’t seem impressed. (10)

‘It rained a great deal and Nellie had expected a grander household’. (11)

Charles was to resign his commission 18 months later on September 3, 1887 and took up farming in partnership with a friend in Sussex.

Paris

For Nellie, the audition with Marchesi was to be the last chance to find out if she could sing.

David Mitchell had already promised her an allowance for 12 months, so Nellie, Annie and George boarded the channel steamer for Paris.

“Flustered and anxious they joined the rush to get on the channel steamer, then battled through an even worse rush to get off. Porters snatched at their luggage, and they could not understand a word anyone said. They arrived at their small hotel and sank, exhausted into French beds.” (12)

The next morning Nellie walked to 88 Rue Jouffroy ready to audition for Madame Marchesi.

Nellie described her first meeting with Marchesi whom she referred to as “the Presence.”

As the door opened and Madame Marchesi entered:

“Terror stuck me to the heart as soon as I saw her. She seemed to me a mixture of alarm and attraction, standing very upright in the middle of the room, dressed all in black, a small grey-haired figure, but one which it was impossible to overlook. And then she smiled, and her whole face, with its long upper lip and its intelligent eyes seem to be transformed. I felt at last that I had found a friend.” (13)

Standing on a tiny platform Nellie said she would sing the aria from La Traviata. Before she had finished, Marchesi stopped and asked why she screeched the top notes and had her sing them piano.

After singing top B, C and E pianissimo, Marchesi suddenly darted out of the room.

It wasn’t until much later that Nellie found out Madame had run upstairs to her husband and told him:

“Salvatore, j’ai enfin une etoile!” ” Salvatore, At last I have found a star!” (14)

Melba describes the day her life changed forever:

“Then the door opened and Madame Marchesi came back, Once more she made me sing, and then she took me by the arm and led me out of the room. And it was then that there came the turning point in my life.

I can see her now, sitting on the sofa by my side, looking me straight in the face, and I can hear her as she said:

“Mrs. Armstrong, are you serious?”

“Yes,” I whispered.

“Alors,” she continued, “if you are serious, and if you can study with me for one year, I will make something extraordinary of you.”

The old lady pronounced the words “extra ordinary” with so much emphasis that I realized she meant what she said, and I felt that at last I had begun.” (15)

Lessons started the next day. After a month, Marchesi put Nellie into the opera class because she had already received several years singing tuition.

To Nellie, Marchesi was her artistic mother, her guide in life and taught the colonial-born Australian the ways of the European world of opera and society.

With limited resources and David Mitchell, Bella and Annie returning to Australia, Marchesi suggested Nellie move into lodgings in Avenue Carnot that were run by a kindly landlady. A nursemaid was found to care for George.

Pamela Vestey graphically describes Nellie’s situation:

“In Paris Nellie was alone as never before, She had confidence in her own ability but now her little boy was her sole responsibility. She would not part with him; he needed her love and the care only she could give him. George was no longer a baby; he adored his father, trying to copy him in every way, but he turned to his mother for security. In spite of her preoccupation with her career she spent much time with him, always able to dispel his fears. His short life had had many changes and he was an anxious little boy. Nellie set herself to work with a dedication that was part hope, part fear. Fear was never to leave her at this time as she thought of the future. In the small high room in the Avenue Carnot she held George close to her, telling him stories of her own childhood to comfort them both.” (16)

For all intents, Nellie was a single working mother living in a foreign country in the 1880s, something very few women of her time would have done.

Nellie split her time between the Avenue Carnot with George, Rue Jouffroy and the Voice.

The Voice had to be trained, cared for and worried about. Nellie’s nasal accent had to be ironed out and the distorted vowels rounded into shape. (17)

Nellie saw her first opera in a real opera house in Paris with Marchesi who continued the careful training of her pupil.

Melba described the event which was a first night at the Paris Opera:

“I stood in the entrance to the foyer, desolated and amazed by the bigness of it all. It seemed to me incredible that so wonderful a place could exist, and when I was sitting in my stall and the curtain had risen, when I heard the first strains of that marvellous orchestra, the first echoes of the perfect chorus, I leaned back in my seat and thought that if I only could sing on that stage for once, I would die happy. The friend at my side, Mlle. Mimaut, turned to me at the end of the First Act and said: “It will not be long before you are singing here, too.”

I laughed out loud.

“What an extraordinary thing to say,” I remarked.

But Mlle. Mimaut was right, for not so very long afterwards I was to make my debut before one of the greatest audiences that the Opera House had ever known.” (18)

Word had spread through operatic circles that Marchesi had a new, talented pupil but society had to wait until December 1886 to hear Nellie in her first performance in Paris – concert at Rue Jouffroy.

While exaggerating, Madame Marchesi claimed that first concert was attended by ‘tout Paris!’ Ambroise Thomas, director of the Paris Conservatoire, composer Charles Gounod, artists the Lemaire sisters, and Mademoiselle Mimaut were present. (19)

It was an influential group of people.

Mrs Armstrong becomes Melba

It was just prior to this concert that the name Melba was selected.

Pamela Vestey writes neither her father nor her husband wanted Nellie to use their names in a theatrical career, so she chose Melba a contraction of her home town of Melbourne. (20)

“At Madame Marchesi’s house all the great men of the artistic world were wont to congregate, and it was her home during my student days that I first met such great men as Gounod, Ambroise Thomas, Debiles, Massenet.” (21)

Two other visitors were to have a profound effect on Melba. One was impresario Maurice Strakosch and the other Monsieurs Dupont and Lapissida, directors of the Brussels Opera.

Strakosch heard Nellie sing and offered her a 10-year contract starting at 1000 francs a month and doubling each year. (22)

While he had no work immediately for her, Nellie realised this was a way of supporting herself and George.

She was to continue her studies and wait for work.

The thought of assured income to supplement her meagre resources saw her sign the contract.

However, a month later, Monsieurs Dupont and Lapissida visited the school. After hearing many of the pupils they asked about “a young Australian, who they say has a beautiful voice.” (23) Nellie sang for them although Madame Marchesi told them she was under contract to Strakosch.

The directors wanted to book Nellie for 3000 francs a month to sing 10 operas a month. Costumes would be supplied. Nellie signed their contract on the advice of Marchesi who said she would talk to Strakosch who was a friend of hers and as he did not have any work for her, they thought he would not notice. (24) But he did notice and was furious. Melba describes the scene with Strakosch after she had explained the situation and thought he would not mind.

“Mind?” he screamed. And then I had to listen for a quarter of an hour to a tirade against the wickedness of Mme. Marchesi, the stupidity of myself and the ingratitude of the world in general to famous impresarios.

Finally the last spasm of rage of was over, and he blew himself out of the room, leaving me to continue my book as he stamped down the five flights of stairs.” (25)

Nellie and George went off to Brussels to prepare for her operatic debut but was served a court order prohibiting her to sing or rehearse at the Théàtre de la Monnaie.

For weeks Nellie and George sat in their little house off the Avenue Louise and waited while Dupont and Lapissida tried to negotiate but to no avail. Even letters to Nellie from Marchesi played down the seriousness of the issue:

“With regard to M. Dupont and M. Lapissida, I approve of their caution. One mustn’t forget that the contract with Strakosch still exists. However, they want to present you to the public of Brussels, not as a member of their company, but as a rising star who gives imposing performances.” (26)

Suddenly, a week before opening night, a miracle occurred or as Melba described it:

“…a stroke of luck like a bolt from the blue, so sensational that ever afterwards I have remembered it when difficulties have been thick about me and the way seemed dark.”

Monsieur Lapissida arrived at her home and blurted out:

“Strakosch est mort! Il est mort hier au soir, dans un cirque. Et je vous attends au Théàtre onze heures!” The impresario had died while at the circus. (27)

Rehearsals began and Melba made her operatic debut at Théàtre de la Monnaie on October 13, 1887.

References

(1) N. Melba, Melodies and Memories, Thornton Butterworth Ltd, London, 1925, pg. 25.

(2) P. Vestey, Melba: A Family Memoir, Pamela Vestey, Coldstream, Melbourne 2000, pg. 27.

(3) T. Radic, Melba The Voice of Australia, The Macmillan Company of Australia Ltd, Melbourne, 1986, pg. 39.

(4) N.Melba, op. cit., pg. 26.

(5) N. Melba, op. cit., pg. 27.

(6) T. Radic, op. cit., pg. 39: Letter to German tenor Rudolph Himmer dated May 13, 1886 and held in the National Library or Australia MS 1496).

(7) N. Melba, op. cit., pg. 28.

(8) T. Radic, op. cit., pg. 42.

(9) http://homepage.eircom.net/~tipperaryfame/leinster.htm

(10) T.Radic, op. cit., pg. 41.

(11) P. Vestey, op. cit., pg. 27.

(12) P. Vestey, op. cit. pg. 28.

(13) N. Melba, op. cit., pg. 29.

(14) N. Melba, op. cit., pg. 31.

(15) N. Melba, op.cit., pg.30-31.

(16) P. Vestey, op. cit., pg. 30.

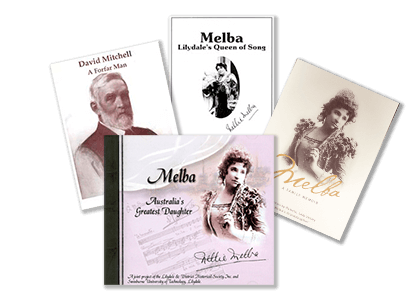

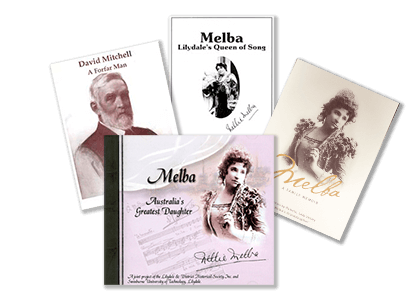

Online Shop

Purchase books, CDs, photographs and other merchandise

Share Your Information with the Museum!

Email us your info (and images) to:

[email protected]

Our home is the Old Lilydale Court House:

61 Castella Street, Lilydale 3140

Hours of opening:

By appointment only:

Fridays 1 to 4pm and Saturdays to Mondays 11am to 4pm.

Sundays are preferred.

Closed Public Holidays

Nellie Melba Museum

Contact Details:

Sue Thompson: 0475 219 884

Email: [email protected]

Share your info with us:

[email protected]

Our home is the Old Lilydale Court House:

61 Castella Street, Lilydale 3140

Hours of opening:

By Appointment only:

Fridays 1 to 4pm and Saturdays to Mondays 11am to 4pm.

Sundays are preferred.

Closed Public Holidays

Nellie Melba Museum

Contact Details:

Sue Thompson: 0475 219 884

[email protected]

Nellie Melba Museum

Contact Details:

Sue Thompson: 0475 219 884

[email protected]

Our home is the Old Lilydale Court House:

61 Castella Street, Lilydale 3140

Hours of opening:

By appointment only:

Fridays 1 to 4pm and Saturdays to Mondays 11am to 4pm.

Sundays are preferred.

Closed Public Holidays

Share Your Information

with Nellie Melba Museum!

Sue Thompson: 0475 219 884

[email protected]