Countries | New Zealand

Towards the end of the 1902 tour, the company successfully toured New Zealand, the conditions were somewhat primitive, Melba was enchanted by her visit to a Maori village. They sang in their beautiful voices to her and gave her a carved small jade figure which became a treasured part of Nellie’s collection of good-luck charms. The party returned to Sydney for a farewell concert, then boarded a ship for England. (1)

In her own words, Melba described her first visit to New Zealand in Melodies and Memories and shows incredible interest and curiosity about the country and people. This remained with her throughout her life as she travelled throughout the world:

In October 1902 (actually February 1903), from Australia I proceeded to New Zealand, and here again I was, in spite of many delightful days, and charming people, to come in contact with a spirit of provincialism which at times made our tour anything but enjoyable.

We arrived in New Zealand after one of those crossings about which the least said the better, and the first person to meet us was a grim-looking gentleman who informed us that he had come from (I believe) the department of Inland Revenue.

‘Very well,’ said John, ‘and what can we do for you?’

To our amazement, this official informed us that they had reckoned out exactly how much we were going to make during our tour. Judged on the basis of full houses every night, and demanded that we should pay, in advance, full income tax on this sum, without allowing us anything for expenses.The astonishing nature of this proposal so took my manager’s breath away that some moments elapsed before he was able to say:

‘But that is preposterous. We haven’t any idea what we shall make. There may be an earthquake. The audiences mayn’t come. Anything might happen.’

‘Very well then,’ said the official, ‘I shall have to come with you and watch your receipts.’

We were perfectly willing that he should do so, though there was something not altogether agreeable – something slightly reminiscent of Prussianism – in the presence of a Government official sitting in our box office at every concert, watching the receipts to see that we did not cheat the revenue of half a crown. I am glad to say that after a time he apparently became persuaded that we were honest, and left us in peace.

Oh, yes, New Zealand was to provide us with many unrehearsed thrills. As you may be aware, parts of New Zealand, following the example of the old United States, are ‘dry,’ and parts are ‘wet.’ I happened, at Invercargill, to be on the prohibition side of the bridge, on the ground floor of my hotel. Within half an hour of my arrival it became only to evident to me that the other side of the bridge was anything but prohibition – in fact, all the night I was kept awake by drunken brawls.

Whether the fact that I was a singer had in any way prejudiced the manager of the hotel against me, I cannot say. But when on the day of my concert I went to him and told him that as I did not eat anything on my singing days, I should be so much obliged if he would let me have a little supper when I returned, he looked at me askance and growled: ‘Supper? You won’t get any supper. You’ve had the last meal you’ll get today. My cook comes on at seven, and goes at seven, and she isn’t going to stay up at night for anybody.’

So that was that! Fortunately, I had a man-servant with me who descended to the kitchens when I returned, and prepared something for me himself.

It was my habit at most of the towns which I visited to sell my autographs for half a crown, and to give the proceeds to local charities. At one place, for some reason or other, only one autograph was sold, so John, naturally, said to me: ‘We can’t very well send this half a crown to charity. We’d better keep it for the next town we visit.’ To which I, innocently enough, agreed.

However, after we had left, an indignant letter arrived from the giver of the half-crown. ‘I’d like to know what you did with the half-crown I sent you,’ he wrote. ‘I didn’t see it in the paper.’ Well, he has seen it in the papers now!Still, in spite of everything, they came to the concerts, and that was all I cared about. In fact, they came in almost embarrassing numbers. At Wellington, the manager of the concert hall told us, by some mischance, that his hall held two hundred more people than it would actually accommodate, and I shall never forget John’s efforts, with tape measures and much exercise of energy, in pushing off arms of chairs and packing the people tighter and tighter. However, we got them in. But I think that if it had not been for the fortunate chance that I possessed a bag of oxygen behind the scenes, with which I occasionally refreshed myself, the breath of huddled humanity would have proved overpowering.

The scene was now set for one of the most beautiful interludes of my life – a period of rich colour and loveliness which seemed, by its very profusion, to be sent as a sort of compensation for the trials and tribulations which had gone before. For the next few days I was to live poetry, to dwell in an atmosphere of peace that seems to come back as I write.

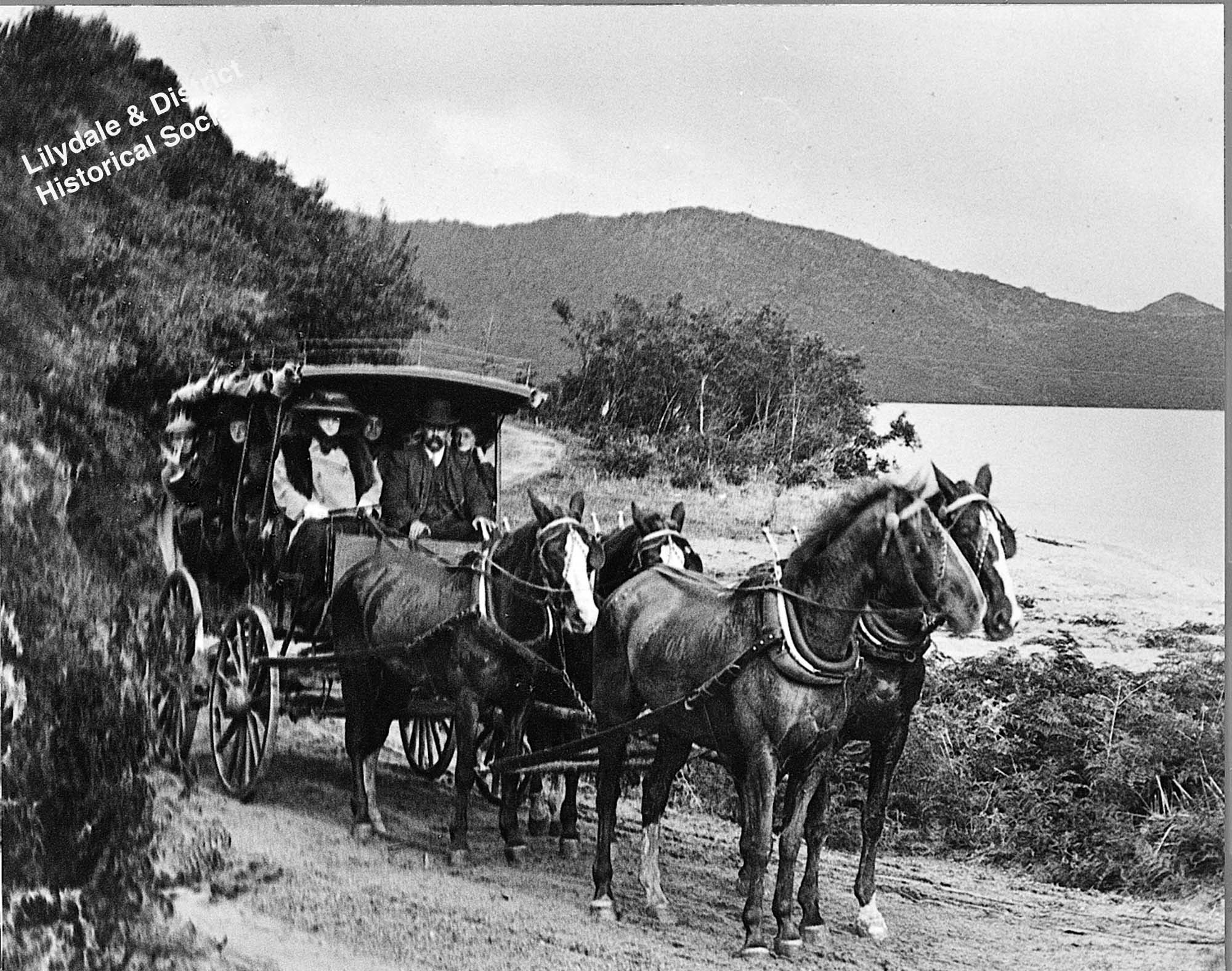

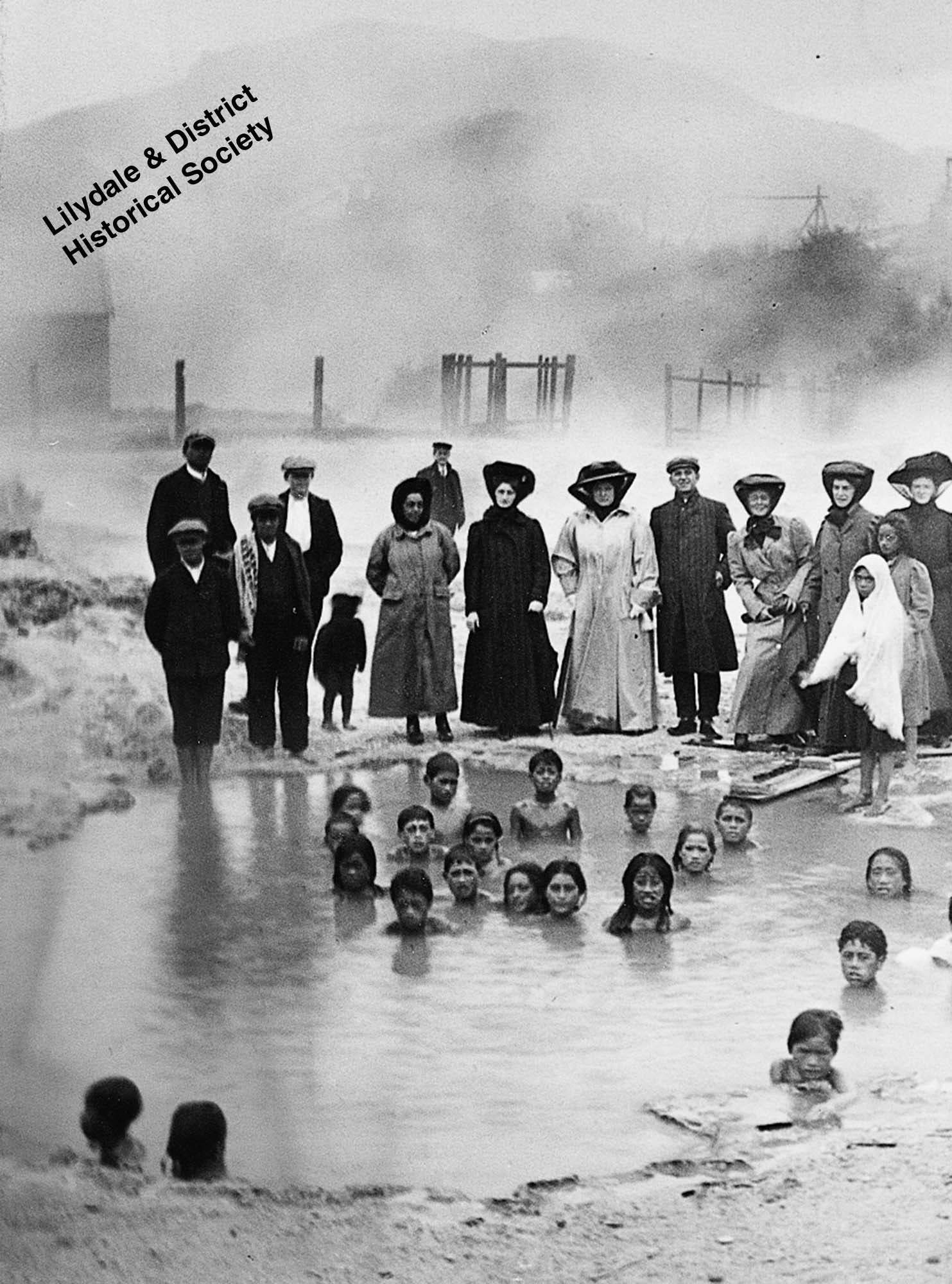

All our concerts were over, and we – that is to say, John and I – set out for the hot lakes. I had heard much of their beauty, but I was not prepared for the uncanny magnificence which greeted us the moment we arrived at the little station of Rotorua. It was dusk as we drove out of the station, and I noticed, all around me, a strange, subdued hissing, as though hundreds of snakes were in the fields. I learnt that this was the hissing of the steam, eternally escaping from the volcanic regions beneath. It is impossible to transcribe the extraordinary effect that this noise had upon one. It never ceases, although sometimes it is loud, sometimes soft, according to the violence of the disturbance.

Even stranger was the heavy scent which charged every breath of air one inhaled, for the air was thick with sulphur fumes. It was as though, in a rash moment, one had descended into the crater of a volcano, and indeed, there was little difference, for all around us were craters, and boiling springs, and seething mud.

At Rotorua there was, at this time, a famous woman guide who rejoiced in the name of Maggie Papakura. Now Maggie as soon as she knew that we were coming had got busy, to prepare for us a welcome, with the result that long before we actually came the name of ‘Melba’ was on every Maori’s lips.

I had hoped to be allowed to come and go unnoticed, but I had not reckoned on the Maori sense of hospitality, for as we came in sight of the hotel there gathered round our carriage, mysteriously dark in the half-light, rows of dusky Maori faces. And I gathered from Maggie Papakura that the chiefs of every Maori tribe in the district had come out to pay me their respects. From behind the trees they came, silently regarding us, their spears in their hands, red flowers in their hair, war paint on their chests, the muscles of their arms and legs gleaming like satin in the flickering torchlight.

Then suddenly one of them leapt in the air, and in a piercing voice, and with a shaking spear, ran toward me, gabbling words which sounded like the most fearful curse that could fall on any human being.

I was terrified and put my hand in the arm of the ubiquitous Maggie.

‘What have I done?’ I said. ‘Why is he so angry?’

‘Be calm, Madame,’ came her soothing voice; ‘he is not angry. He is saying, welcome, welcome, welcome.’

I sighed with relief, only to start again as another chief sprang from the shadows.

‘He is telling you,’ said Maggie, when he had finished, ‘that he is welcoming you as though you were the Queen of England.’

And I realised, for not perhaps the first time, that royalty has its anxieties as well as its triumphs.

If an artist had been painting my arrival, his brush would have been stained with black and crimson. But on the second day he would have been prodigal with white and gold. For when we drove out, in the early morning, the sun was shining brightly and from time to time we would hear, from a neighbouring hillock, the sound of sweet singing. Looking up, I saw a group of native girls, clad in white, with wreaths of flowers in their hair, and echoing down to me, with the eternal accompaniment of the hissing steam:

Haere-mai, Madame Melba

Haere-mai, Madame Melba

And when they had finished singing, they threw to me, like fairy snow, heavy white blossoms from above.

I turned to Maggie Papakura, who again was standing by my side, in her gorgeous Maori costume:

‘Tell me ,’ I said, ‘what is it they are singing?’

‘It is but a song of welcome, Madame,’ she replied, and at the same time she stepped out into the road and in a sweet crooning voice delivered one of the most charming little speeches I have ever heard. When it was over, we bid the Maori girls good-day, and went on to refresh ourselves from time to time with fruit, and a draught of the wonderful, slightly sulphur-flavoured water that bubbled up in endless streams.

If only I could transcribe some of the events of those days as I saw them, half the population of the world would take the next steamer to New Zealand.

On the third day, had any artist been travelling with us, he would have had to use every colour he possessed.

The beauty of it all! We drove up through the mountains, immense ferns brushing the wheels of our coach, emerald mosses glistening in the shadows, until we reached the remains of the village of Wairoa, which was destroyed years ago by the eruption of Mount Tarawera, which literally split in half, deluging the whole surrounding country in lava and boiling mud.And then we went on farther until we came to the most astounding sight of all – a lake of azure blue side by side with a lake of palest green. How or why these lakes, which are only flooded waters, should vary so in colour, since they are only separated by a few yards of earth, is a mystery to all scientists, and so I am not likely to be able to elucidate it. I only know that it filled me with a feeling of the deepest wonder.

References

(1) P. Vestey, Melba A Family Memoir, Pamela Vestey, Coldstream 2000, page 112.

(2) N. Melba, Melodies and Memories. The Autobiography of Nellie Melba. Introduced and Annotated by John Cargher, pgs 149 to 153.

Online Shop

Purchase books, CDs, photographs and other merchandise

Share Your Information with the Museum!

Email us your info (and images) to:

[email protected]

Our home is the Old Lilydale Court House:

61 Castella Street, Lilydale 3140

Hours of opening:

By appointment only:

Fridays 1 to 4pm and Saturdays to Mondays 11am to 4pm.

Sundays are preferred.

Closed Public Holidays

Nellie Melba Museum

Contact Details:

Sue Thompson: 0475 219 884

Email: [email protected]

Share your info with us:

[email protected]

Our home is the Old Lilydale Court House:

61 Castella Street, Lilydale 3140

Hours of opening:

By Appointment only:

Fridays 1 to 4pm and Saturdays to Mondays 11am to 4pm.

Sundays are preferred.

Closed Public Holidays

Nellie Melba Museum

Contact Details:

Sue Thompson: 0475 219 884

[email protected]

Nellie Melba Museum

Contact Details:

Sue Thompson: 0475 219 884

[email protected]

Our home is the Old Lilydale Court House:

61 Castella Street, Lilydale 3140

Hours of opening:

By appointment only:

Fridays 1 to 4pm and Saturdays to Mondays 11am to 4pm.

Sundays are preferred.

Closed Public Holidays

Share Your Information

with Nellie Melba Museum!

Sue Thompson: 0475 219 884

[email protected]